For first-time UHF radio buyers, the range of options can seem overwhelming. Handheld or fixed-mount? How many watts of transmission power? What dBi antenna? Do higher numbers mean more range? Is simply going with more always better?

There are dozens of potential combinations, but at the end of the day, all you really want to know is how far can I communicate. Unfortunately, much of the marketing and packaging information that goes along with UHF radios is often unhelpful at best, or misleading at worst.

Above image credit: Ronny Dahl

Ultra-high frequency (UHF) radios 101

Without going into overly technical details, there are only a few points you really need to know to understand UHF communication.

1) Radio wattage – The wattage of your radio is its transmission power. The higher the wattage, the farther it can potentially transmit.

Note: A higher wattage does not increase the distance at which you can receive transmissions, it only increases your outbound transmissions. At the edge of usable 5w range, if you have a 5w radio and your mate has a 3w radio, they would be able to hear you, but you would not be able to hear their replies due to their lower transmission power.

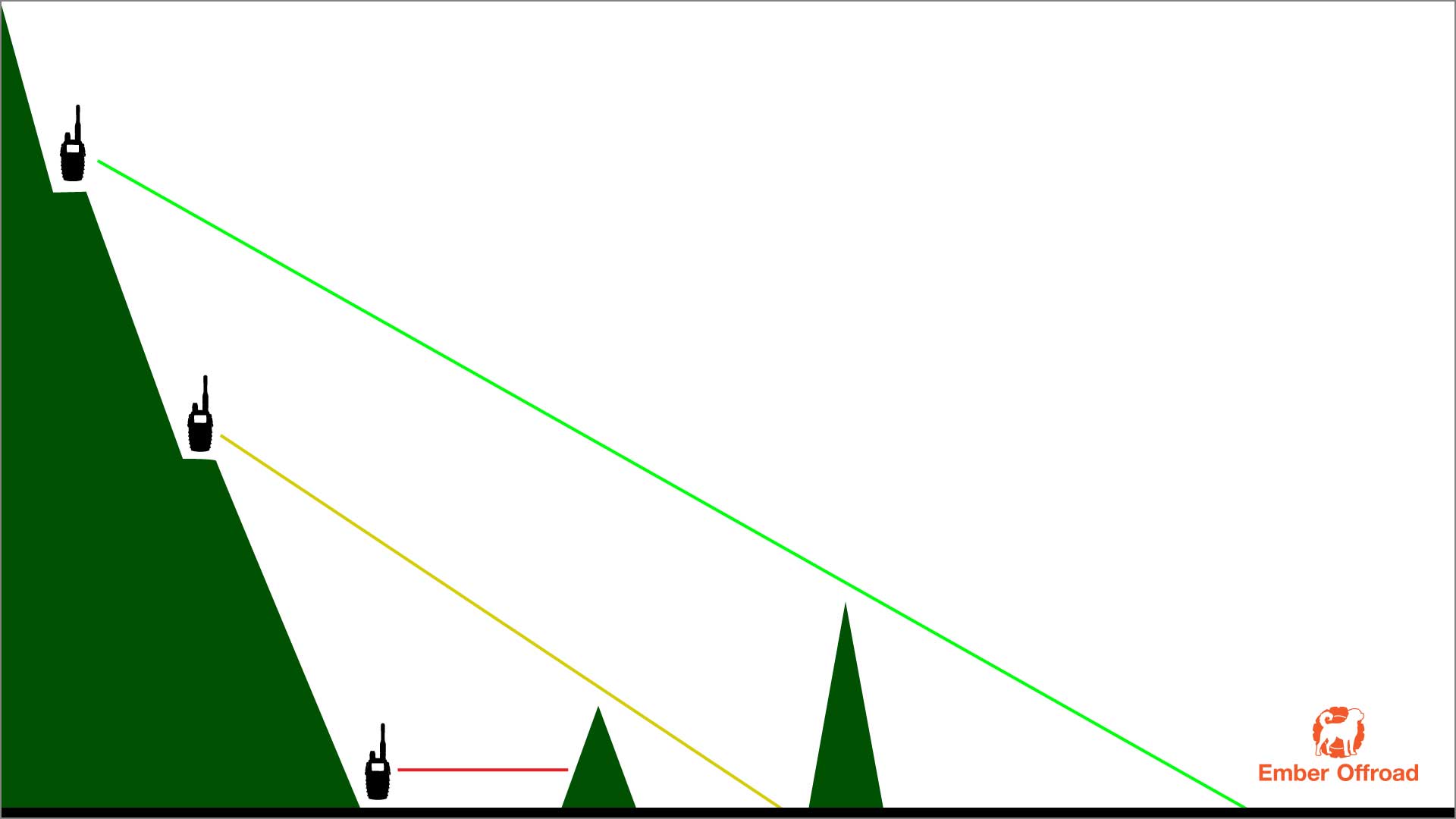

2) Line of sight (LOS) – UHF radio waves travel primarily by line of sight. They do not bounce around corners to find their way from one end of a city to another, and they do not curve over mountains.

They travel straight (with some ground reflection included), and attempt to pass through any obstructions between the transmitter and the receiver; the more obstructions between them, the weaker the signal becomes for the recipient, and the shorter the range.

Buildings, hills, trees, rocky outcrops, other vehicles, etc. all create obstructions for UHF radios. Even heavy rain or large volumes of dust in the air from strong winds can negatively impact the range.

Technically there is some reflection of UHF from the upper atmosphere, but it’s so weak that it’s a moot point; if there’s a mountain between you and your mate, the sky won’t solve your problem.

3) Antenna Gain and dBi – Consumer UHF antennas come in 3 groups, ranging roughly from around 2-8 dBi, depending on the manufacturer. These are:

- Unity gain: 2.1-3 dBi antennas are common for this range.

- Medium gain: 6.6 dBi is arguably the standard medium gain antenna.

- High gain: 8-9 dBi antennas are common for this range.

Note: You may see antennas measured as dB or dBi, which are different methodologies of measuring gain, but this is getting overly technical for the purpose of this article, and the same fundamentals apply.

In short, the higher the gain an an antenna the farther it can transmit, but, the more susceptible it is to obstruction and interference; the gain of an antenna also shapes its “radiation pattern” which affects how it performs in different environments.

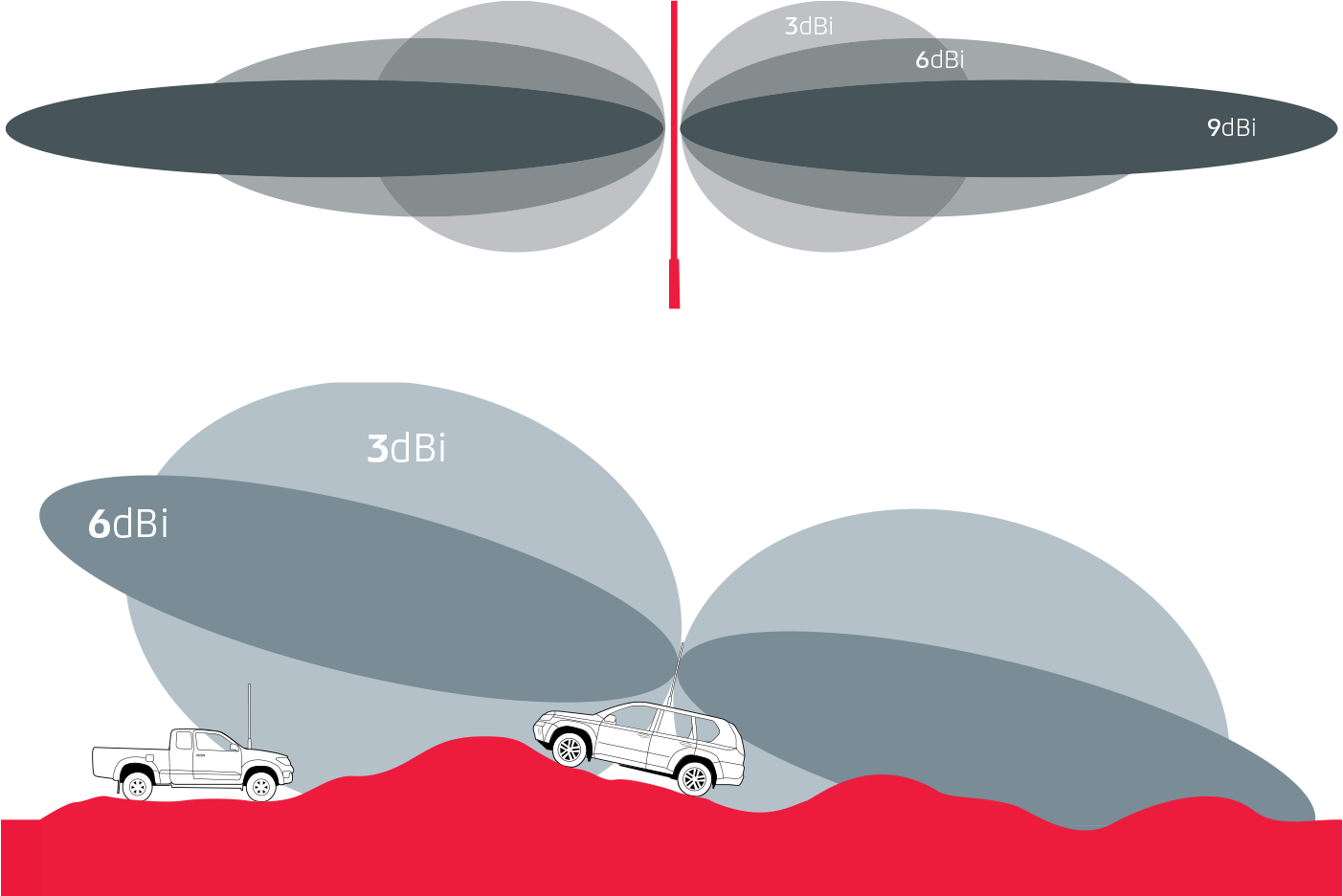

UHF radio and antenna manufacturer GME have created a great visual representation of this, which you can see below:

The top is a representation of the radiation pattern and range of 3, 6, and 9 dBi antennas respectively, while the bottom picture demonstrates how a higher dBi can be less effective in certain situations, despite transmitting farther.

This is where selecting the right antenna for your application comes in. As general rules of thumb for selecting the right antenna:

- If you’re off-roading through mountains and valleys, a 2.1 dBi will be best.

- If you’re traveling vast open distances, outback travels like a flat desert, and 8-9 dBi antenna will be best (but it will be 2+ meters tall, so don’t plan on going into any carparks).

- 6.6 dBi is a compromise of both the above and will provide a balance of range and tolerance for interference. 6.6 dBi potentially works best for things like traveling distances on undulating roads where there will be some landscape interference, and country roads with trees, but nothing as dramatic as the sheer wall a mountain creates.

If you only want to run with a single antenna for all situations, 6.6 dBi is probably your best bet, as it will offer modest performance across the board. If you regularly travel a variety of environments and want to maximize performance, you’ll need to invest in multiple antennas.

4) Antenna mounting height – This is more of a situational note, but worth mentioning. An antenna mounted higher will perform better than an identical antenna mounted lower, as it will have some additional clearance of ground obstructions.

e.g. An antenna mounted on the roof rack of a 4WD will perform slightly better than one mounted on the bull bar.

The radio of a four-wheel-drive parked at an elevation 200 meters up a mountain and transmitting into the open will perform significantly better than the same vehicle parked at the base of the mountain.

Marketing vs reality

As we touched on at the start, the ranges quoted on the packaging aren’t always the most helpful in real-world situations. To quote one brand on one of their 5w handheld radios:

The ******* series can communicate up to a 17km range allowing users to stay connected on their next adventure even in the most remote locations without mobile reception.

The key phrase here is “up to”. Now, I don’t doubt that under ideal conditions, a signal can be detected between 2 of these radios at 17km and that the statement is technically accurate.

But it’s certainly not going to be crystal clear, you’re going to be trying to pick out the conversation from a storm of static. And when was the last time you and a mate stood at the top of two mountains 17km apart on a clear blue sky day wanting to talk to each other? I’m going to guess never.

As soon as you’re in real driving and offroad conditions, “up to” goes out the window.

Real-world examples, situations, and range

As already mentioned, there are dozens of possible setup combinations and environment scenarios, it would be a full-length novel to cover them all, so let’s define a common setup for the purpose of example.

I think it’s fair to say the most common setup for a four-wheel-drive is a fixed mount 5w radio unit, with a 2.1 dBi antenna, mounted on the bull bar. Let’s use this as our first example.

Situation #1: Convoys and open tracks

In road convoys where you’re no more than a few hundred meters away from each other, your setup really isn’t going to make a difference. At these short distances, with minimal interference between you, any radios (fixed or handheld) from a quality manufacturer like GME or Uniden, etc. will communicate fine.

Likewise for doing off-road trails as a group. If you’re spaced out along a track but traveling together you shouldn’t have any communication problems.

(I make no promises for eBay bargain radios)

Situation #2: Twisting mountain tracks, and finding each other

If traveling winding tracks together as a group, for the most part, the above information still applies.

If you’re a bit further spread out, e.g. a straggler coming up the trail 500 meters behind and around a bend or two, you’ll almost certainly lose some signal quality, and pick up some static, but should still be able to reach your travel mates with little issue.

If you’re a late arrival to camp, and starting to radio ahead in order to make contact and locate your travel mates, you’ll probably make contact somewhere around the 1-2 km mark (0.6 -1.2 miles). This can be very subject to terrain though, you may get more, or you may get less, depending on how open or obstructive the mountainscape is.

Situation #3: The open road

In my experience, on flat open highways with a 5w radio and 2.1 dBi GME antenna mounted on the roof rack, the maximum range is about 11-12 km (about 7 miles).

And by maximum, I mean just usable, it’s not clear, there’s plenty of static, and there’s going to be a lot of “can you say that again?”.

With my 6.6 dBi antenna on instead, the maximum range is extended by around 2km (1.2 miles), but noticeable static and loss of signal also start to occur about 2km earlier than with the 2.1 dBi antenna. Even in near-ideal settings, the lower tolerance for interference of the higher gain antenna is noticeable.

Picking the right combination for you.

As will be clear by now, the “up to” range written on most radio packaging is basically useless. Forget that, and pick a combination that best suits where you intend to use your radio.

If you want maximum range, go with a 5w radio (or whatever the highest legal wattage is in your country/state, as there are limits). If you’re only going to be communicating in a convey or wandering close to camp, a 2-3w radio should serve just as well (or even a 1w radio, but for the minimal price difference you might as well buy a 3w, in my opinion).

For the antenna, pick the right antenna for your application, as listed above.

Read section again:

Ultra high frequency (UHF) radios 101

Marketing vs reality

Real world examples

Selecting the right antenna for your application

# UHF radio range, UHF interference, which UHF radio to buy, which UHF antenna to buy.